Security of Payment -Contents

The Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 2002 (VIC) – or, as most people call it ‘Security of Payment Act’, is a Victorian-specific legislation that is intended to reduce the incidence of insolvency in the construction industry. It does this by:

All States and Territories in Australia now have security of payment legislation. However, there are differences from State-to-State. This page relates to the Security of Payment Act in Victoria only. If you wish to read about NSW, click here. Otherwise, find your state in our general page here.

Section 7 of the Act explains who is covered. Broadly, most commercial construction contracts will be caught by the legislation. Residential building work is excluded where the principal resides in, or proposes to reside in, the premises where the work is performed.

Meet with a senior construction lawyer and learn how to best protect your position

The main protections given to contractors in Victoria are:

You can read more about this here.

The process starts with the contractor making a ‘payment claim’ in relation to the claimed amount.

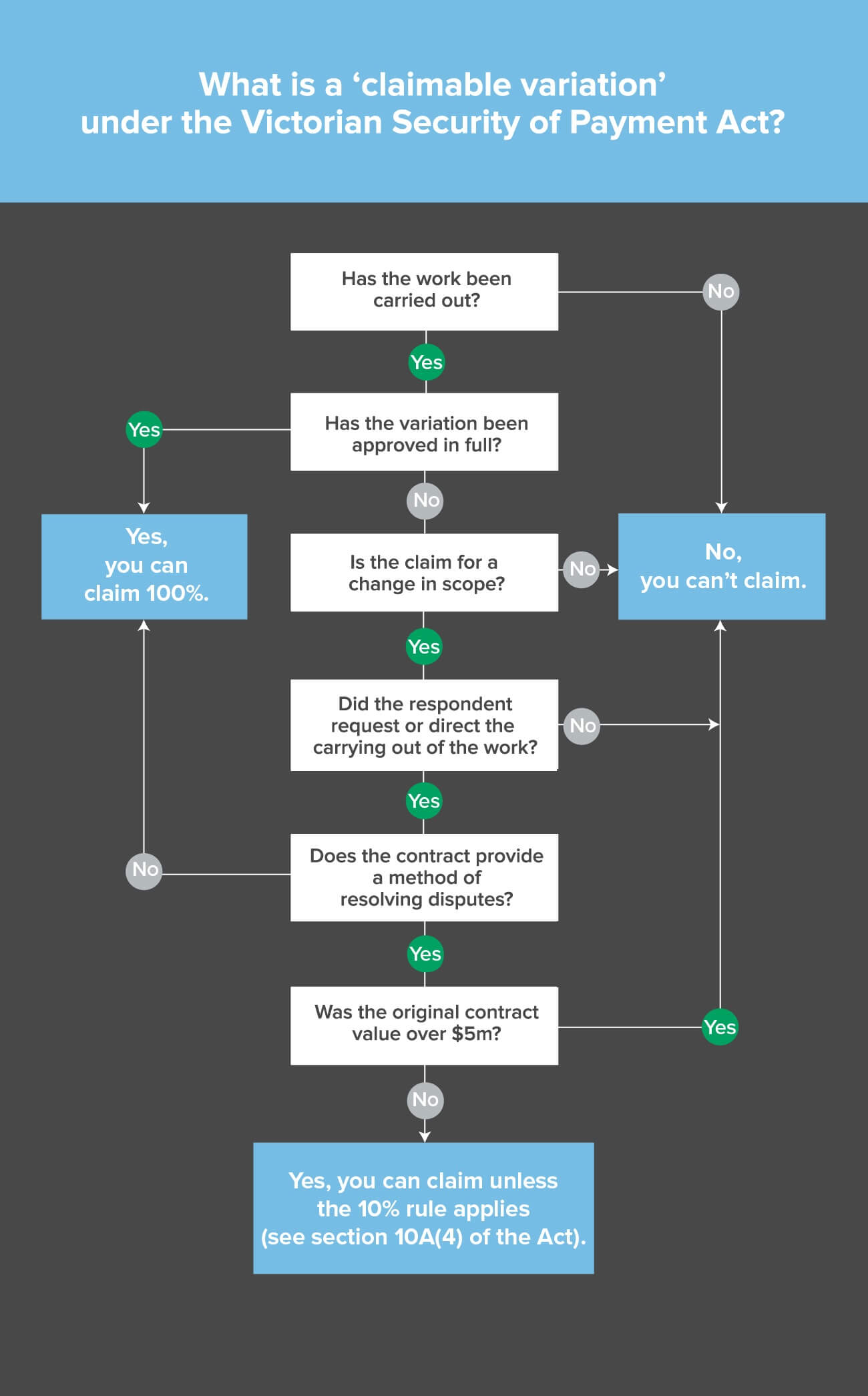

The Act only allows for certain variations to form part of the claimed amount. These are called 'claimable variations'. There are two classes of claimable variations – agreed variations (class 1) and disputed variations (class 2). The graphic below explains what a ‘claimable variations’ is.

A variation falls into class 1, and may be claimed in a payment claim in full, if the parties agree on all of the following:

A variation is classified as a class 2 variation if it is not a class 1 variation and where:

Additionally, a disputed variation will only be claimable if it meets certain threshold criteria and if the contract does not contain a ‘method of resolving disputes’. You can read about those threshold criteria here.

The Act expressly excludes certain amounts from being claimed in a payment claim. These are called 'excluded amounts'. Excluded amounts will not be taken into account by an adjudicator.

An excluded amount is any amount that:

A payment claim cannot be made under the Security of Payment Act without an available 'reference date' – being a date fixed by the contract or the legislation as a date for making payment claims. It must be served within 3 months after the reference date or the period specified in the contract (whichever is later). A sample payment claim form published by the Victorian Building Authority can be found here.

Once a payment claim has been made, the principal (or head contractor) only has 10 business days to respond, unless the contract prescribes a shorter period. This response must be in writing and is called a 'payment schedule'. A sample payment schedule published by the Victorian Building Authority can be found here.

If the principal or head contractor fails to provide a payment schedule within the required timeframe, it will be liable for the entire amount of the claim. The contractor can then recover this amount as a debt in court.

If the principal issues a payment schedule but the contractor disagrees with the assessment, the contractor can make an 'adjudication application'. We explain this further below.

Adjudication is a streamlined process that allows a contractor to recover a disputed or unpaid progress payment. The dispute is determined by an independent adjudicator.

The adjudicator is not a judge (and is often not a lawyer), and is appointed by an independent ‘nominating authority’. You can find a list of nominating authorities in Victoria here.

The adjudication application is a written document that must be sent to the nominating authority within a fixed period – usually 10 business days from the date the payment schedule is served on the principal or head contractor. The exact timeframe will depend on the circumstances. (You can find the relevant part of the legislation here).

Any response to an adjudication application must be made within 5 business days of receiving the application, or 2 business days after receiving notice of the adjudicator having accepted their appointment, whichever is longer. This is often an exceptionally short timeframe.

Once the time for a response has lapsed, the adjudicator is required to determine the application. Typically, this is done by reference to the application and the response, with neither party having any right to appear before the adjudicator. It is not uncommon for the adjudicator to seek further submissions from the parties.

Adjudication determinations are usually issued within 10 business days of the date the adjudication response was required (although extensions are often sought by the adjudicator and approved by the parties). You can read more about this here.

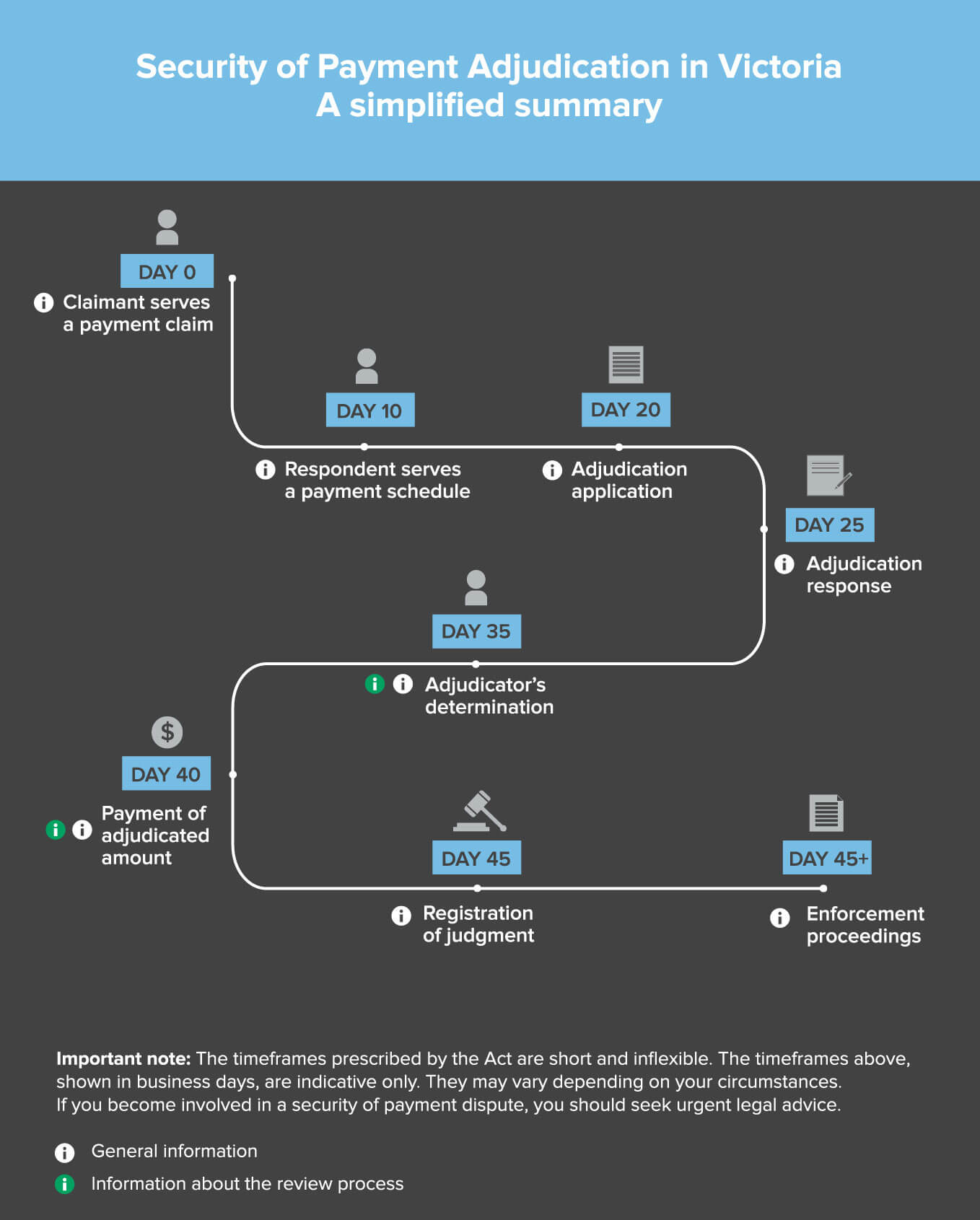

This must be done on and from a ‘reference date’. Otherwise the claim will be invalid. A payment claim must be served within the period set out in the contract or 3 months after the ‘reference date’ (whichever is later). The claimed amount cannot include any excluded amounts (See s14(3)(b)).

The time period can be shorter depending on the contract. All reasons for withholding payment must be included. If a payment schedule is not served within the period, the respondent will be liable for the claimed amount.

This must occur within 10 business days of receiving the payment schedule. Different options apply if no payment schedule is received within the required timeframe.

This must be made within 5 business days of receiving the application, or 2 business days after receiving notice of the adjudicator’s appointment, whichever is later.

This is due 10 business days after the adjudicator accepts the application, unless the parties agree to an extension. Adjudicators will not release their determination until their fees have been paid by the claimant. (The adjudicator can determine that those costs be reimbursed by the respondent).

If the adjudicated amount exceeds $100,000, either party can request a review of any ‘excluded amounts’ wrongfully allowed or excluded by the adjudicator. This may take up to 15 business days. (The timeframes in this chart ignore the potential impact of a review).

Payment is required within 5 business days of the adjudication determination being released.

The respondent may be required to make a payment before applying for a review (See s28B).

If payment is not made as required, the claimant can obtain an ‘adjudication certificate’ and register it in court as a judgment. If the claimed amount includes excluded amounts, a court will not register a judgment in favour of the claimant unless it is satisfied that the claimed amount does not include any excluded amount.

If still unpaid, the claimant can take proceedings to enforce the judgment (eg winding up application, garnishee order etc).

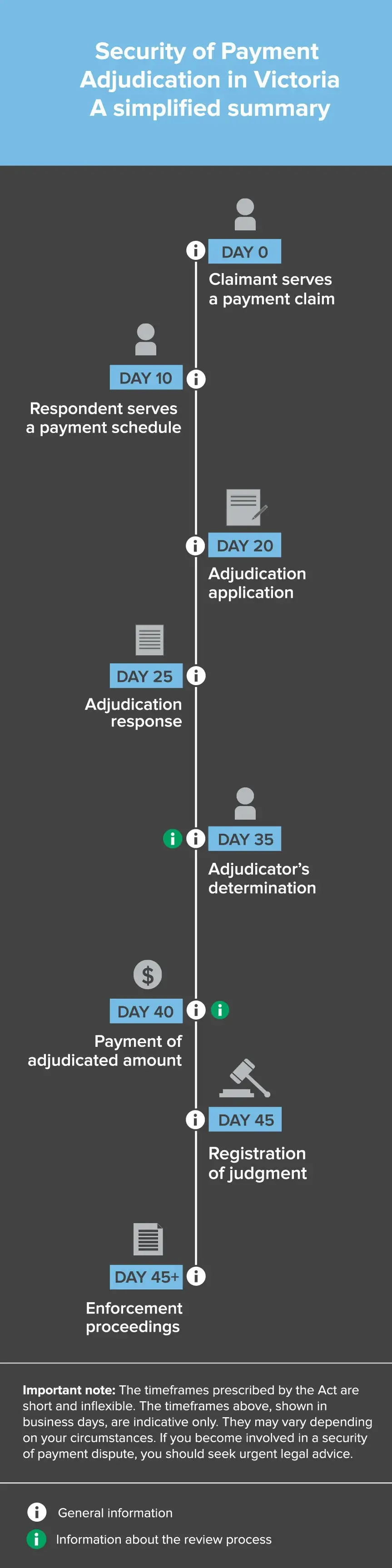

This must be done on and from a ‘reference date’. Otherwise the claim will be invalid. A payment claim must be served within the period set out in the contract or 3 months after the ‘reference date’ (whichever is later). The claimed amount cannot include any excluded amounts (See s14(3)(b)).

The time period can be shorter depending on the contract. All reasons for withholding payment must be included. If a payment schedule is not served within the period, the respondent will be liable for the claimed amount.

This must occur within 10 business days of receiving the payment schedule. Different options apply if no payment schedule is received within the required timeframe.

This must be made within 5 business days of receiving the application, or 2 business days after receiving notice of the adjudicator’s appointment, whichever is later.

This is due 10 business days after the adjudicator accepts the application, unless the parties agree to an extension. Adjudicators will not release their determination until their fees have been paid by the claimant. (The adjudicator can determine that those costs be reimbursed by the respondent).

If the adjudicated amount exceeds $100,000, either party can request a review of any ‘excluded amounts’ wrongfully allowed or excluded by the adjudicator. This may take up to 15 business days. (The timeframes in this chart ignore the potential impact of a review).

Payment is required within 5 business days of the adjudication determination being released.

The respondent may be required to make a payment before applying for a review (See s28B).

If payment is not made as required, the claimant can obtain an ‘adjudication certificate’ and register it in court as a judgment. If the claimed amount includes excluded amounts, a court will not register a judgment in favour of the claimant unless it is satisfied that the claimed amount does not include any excluded amount.

If still unpaid, the claimant can take proceedings to enforce the judgment (eg winding up application, garnishee order etc).

In limited circumstances, either party may apply for an adjudicator’s determination to be reviewed. A determination may be reviewed where:

A respondent can seek a review of the determination if:

A claimant can only seek a review of the determination where the adjudicator has failed to include an amount in its determination because it was wrongly identified as an ‘excluded amount’.

The other party to an adjudication review has three business days after the applicant sends them a copy of the application to make submissions to the authorised nominating authority in response.

The application for review must be made by the authorised nominating authority within five business days after receiving the adjudication determination. The authorised nominating authority will appoint a new adjudicator and notify the parties within five business days of receiving the application. The review adjudicator must complete the review within five business days of accepting appointment (or 10 business days if the claimant agrees).

Once an adjudication determination has been made, the respondent must pay the ‘adjudicated amount'. If it does not:

If the judgment debt is not paid, the contractor can then commence debt recovery proceedings.

The entry and enforcement of an adjudication certificate can have negative implications for the respondent’s credit rating and, if it is a head contractor, its ability to secure future work. This is because some principals and government bodies will take this type of behaviour into account when awarding tenders.

If the principal is insolvent, an adjudication determination may not be worth much unless it can be enforced against another party.

In Victoria, the Act allows subcontractors to recover the adjudicated amount out of money that is payable to a head contractor by its principal for construction work or goods and services that the principal engaged the head contractor to carry out. That is, it allows a subcontractor to redirect payments that would ordinarily be made by the principal to the head contractor so that the subcontractor receives the payment instead of the head contractor.

Before a subcontractor can obtain the money owed from the principal:

Once a notice of claim is served, the principal must pay the subcontractor the money that it owes the head contractor. If the principal fails to pay, the subcontractor may sue the principal to recover the debt in court.

The parties to an adjudication must each bear their own costs. That is, you will not be able to recover any costs you incur in preparing or responding to an adjudication application from the other side.

If you are the claimant, you will need to pay the adjudicator’s costs before he or she releases a determination. If you are successful, the adjudicator will normally allow you to recover most or all of those costs from the other side. Those costs form part of the adjudication certificate if they are not immediately paid by the respondent.

Yes, however the circumstances in which they can be appealed are extremely limited.

The mere fact that an adjudicator makes a mistake is usually not a sufficient reason for a determination to be set aside.

To be able to set aside a determination, you would generally need to prove some form of ‘jurisdictional error’. A jurisdictional error is an error that involves the adjudicator having acted outside the scope of his or her authority, such as by:

You can read more about this here.

Any payment made under the security of payment legislation is an interim payment only.

If the contractor recovers more under the security of payment legislation than it would be entitled to receive under the contract, the principal (or head contractor) will have a contractual right to recover the difference.

This interim nature of the payment is reflected in the name of the legislation. Also, when the legislation was originally passed, respondents had the option to pay the adjudicated amount into court pending the final determination of the dispute. Unless there are exceptional circumstances (potentially including the insolvency of the claimant), that is no longer the case.

Level 22, Sydney Place, 180 George Street, Sydney NSW 2000

P: +61 2 9229 2922 | E: info@turtons.com

Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.